Recent News

Legal Elements and Sentencing Guidelines For Corruption

Sep 06, 2023Corruption

It is no secret that the law, as well as criminal lawyers, takes corruption very seriously. Singapore is one of the least corrupted countries in the world. However, there are still instances of corruption which seep through the system. This short article will discuss the salient legal elements of corruption. It will also explore the sentencing framework for corruption in the context of the agent-principal relationship.

Agent-Principal Relationship

To help set the context, a situation of corruption often involves the following three parties:

- Party A – the briber

- Party B – the recipient of the bribe

- Party C – the person to whom B owes a duty.

The following fictitious example illustrates a simple situation of corruption:

Party A runs a business importing bananas. To import bananas, Party A requires a license. Party B works at the Banana Licensing Authority (“BLA”) – the BLA is in charge of issuing banana import licences to businesses. Party A knows that his chances of getting a license is low, given that his bananas are of sub-par quality. Party A then approaches Party B and offers to pay Party B $10,000 in exchange for a banana import license. Party B accepts the money and, in breach of his duty to the BLA, issues a banana import license to Party A.

The forecited example is a clear example of corruption within the meaning of Section 6 of the Prevention of Corruption Act (“PCA”), which reads as follows:

“If —

- any agent corruptly accepts or obtains, or agrees to accept or attempts to obtain, from any person, for himself or for any other person, any gratification as an inducement or reward for doing or forbearing to do, or for having done or forborne to do, any act in relation to his principal’s affairs or business, or for showing or forbearing to show favour or disfavour to any person in relation to his principal’s affairs or business;

- any person corruptly gives or agrees to give or offers any gratification to any agent as an inducement or reward for doing or forbearing to do, or for having done or forborne to do any act in relation to his principal’s affairs or business, or for showing or forbearing to show favour or disfavour to any person in relation to his principal’s affairs or business; or

- any person knowingly gives to an agent, or if an agent knowingly uses with intent to deceive his principal, any receipt, account or other document in respect of which the principal is interested, and which contains any statement which is false or erroneous or defective in any material particular, and which to his knowledge is intended to mislead the principal,

he shall be guilty of an offence and shall be liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding $100,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 5 years or to both.”

The elements of an offence under Section 6 of the PCA are set out below:

- acceptance of gratification;

- as an inducement or reward (for any act, favour or disfavour to any person in relation to the recipient’s principal’s affairs or business);

- there was an objective corrupt element in the transaction; and

- the recipient accepted the gratification with guilty knowledge.

In essence, the recipient must have received the gratification believing that it was given to him in exchange for conferring a dishonest gain or advantage on the giver in relation to his principal’s affairs.

It should also be noted that “gratification” is given a broad meaning in Section 2 of the PCA, and it can take the form of (this is a non-exhaustive list): (a) money; (b) any office, employment or contract; (c) sexual favours; (d) any favour or advantage of any description.

No Agent-Principal Relationship

At this juncture, it ought to be highlighted that corruption can also take place where there is no agent-principal relationship. For instance, if party A pays party B a sum of $10,000 for party B to take the rap for an offence that party A committed, that would still be corruption. Such types of corruption will fall within the meaning of Section 5 of the PCA, which reads as follows:

“Any person who shall by himself or by or in conjunction with any other person —

- corruptly solicit or receive, or agree to receive for himself, or for any other person, any gratification as an inducement to or reward for, or otherwise on account of —

- any person doing or forbearing to do anything in respect of any matter or transaction whatsoever, actual or proposed; or

- any member, officer or servant of a public body doing or forbearing to do anything in respect of any matter or transaction whatsoever, actual or proposed, in which such public body is concerned; or

- corruptly give, promise or offer to any person whether for the benefit of that person or of another person, any gratification as an inducement to or reward for, or otherwise on account of —

- any person doing or forbearing to do anything in respect of any matter or transaction whatsoever, actual or proposed; or

- any member, officer or servant of a public body doing or forbearing to do anything in respect of any matter or transaction whatsoever, actual or proposed, in which such public body is concerned,

shall be guilty of an offence and shall be liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding $100,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 5 years or to both.”

Categories of Corruption

The Courts have identified 3 broad categories of corruption (applicable in both private and public sector corruption cases):

- First, where the receiving party is paid to confer on the paying party a benefit that is within the receiving party’s power to confer, without regard to whether the paying party ought properly to have received that benefit. This is typically done at the payer’s behest.

Example: where the receiving party purchases or favourably recommends the goods or services offered by the paying party.

- Second, where the receiving party is paid to forbear from performing what he is duty bound to do, thereby conferring a benefit on the paying party. Such benefit typically takes the form of avoiding prejudice which would be occasioned to the paying party if the receiving party discharged his duty as he ought to have. This also is typically done at the payer’s behest.

Example: where the receiving party, who is under a duty to inspect the paying party’s goods or work, slackens in his inspection or turns a blind eye to any deficiencies in the paying party’s goods or work.

- Third, where a receiving party is paid so that he will forbear from inflicting harm on the paying party, even though there may be no lawful basis for the infliction of such harm. This is typically done at the receiving party’s behest.

Example: where a bribe is solicited by a person who receives applications for licences or permits, to ensure that an applicant’s application is timeously processed and not somehow inexplicably misplaced

Punishment for Corruption

From the outset, it is highlighted that the punishment for public sector corruption is more severe than private sector corruption. Section 6 (and 5) of the PCA provides the applicable punishment for private sector corruption – i.e., a fine not exceeding $100,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 5 years or to both.

However, where public sector corruption is involved, the punishment is a fine not exceeding $100,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 7 years or to both:

Section 7 of the PCA

“A person convicted of an offence under section 5 or 6 shall, where the matter or transaction in relation to which the offence was committed was a contract or a proposal for a contract with the Government or any department thereof or with any public body or a subcontract to execute any work comprised in such a contract, be liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding $100,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 7 years or to both.”

There are good policy reasons behind the difference in punishment. Eradicating corruption has always been a primary concern. This concern becomes all the more urgent where public servants are involved, whose very core duties are to ensure the smooth administration and functioning of the country.

Private Sector Corruption Sentencing Guideline

The applicable sentencing framework for private sector corruption offences under Section 6 of the PCA involves, broadly, the following steps:

First, the Court will consider the following (non-exhaustive) offence-specific factors:

| Offence Specific Factors |

| Factors going towards harm | Factors going towards culpability |

| – actual loss caused to principal – benefit to the giver of gratification – type and extent of loss to third parties – public disquiet – offences committed as part of a group or syndicate – involvement of a transnational element – whether the public service rationale is engaged – presence of public health or safety risks – involvement of a strategic industry – bribery of a foreign public official | – amount of gratification given or received – degree of planning and premeditation – level of sophistication – duration of offending – extent of the offender’s abuse of position and breach of trust – offender’s motive in committing the offence – presence of threats, pressure or coercion – the role played by the offender in the corrupt transaction |

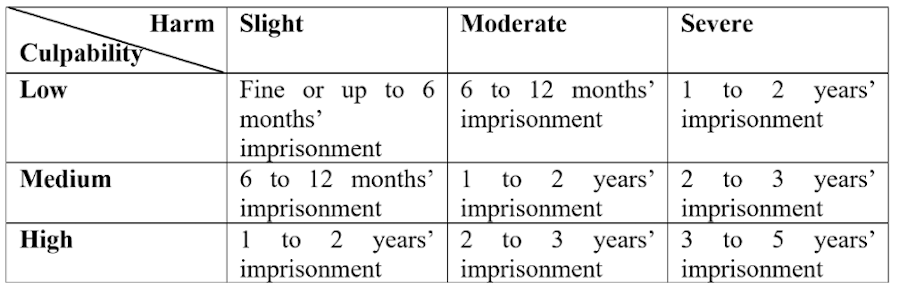

Second, based on the forecited factors, the Court will determine the indicative starting sentencing range:

Lastly, the Court will make further adjustments to the indicative starting sentencing range by considering the relevant aggravating and mitigating factors. A common aggravating factors is an offender’s relevant antecedents. While a common mitigating factor is the offender’s genuine remorse over the commission of the offence.

Public Sector Corruption

The applicable sentencing framework for public sector corruption offences under Section 6 read with Section 7 of the PCA involves, broadly, the following steps:

First, the Court will consider the following (non-exhaustive) offence-specific factors:

| Offence Specific Factors |

| Factors going towards harm | Factors going towards culpability |

| – actual loss caused to principal – benefit to the giver of gratification – type and extent of loss to third parties – public disquiet – offences committed as part of a group or syndicate – involvement of a transnational element | – amount of gratification given or received – degree of planning and premeditation – level of sophistication – duration of offending – extent of the offender’s abuse of position and breach of trust – offender’s motive in committing the offence |

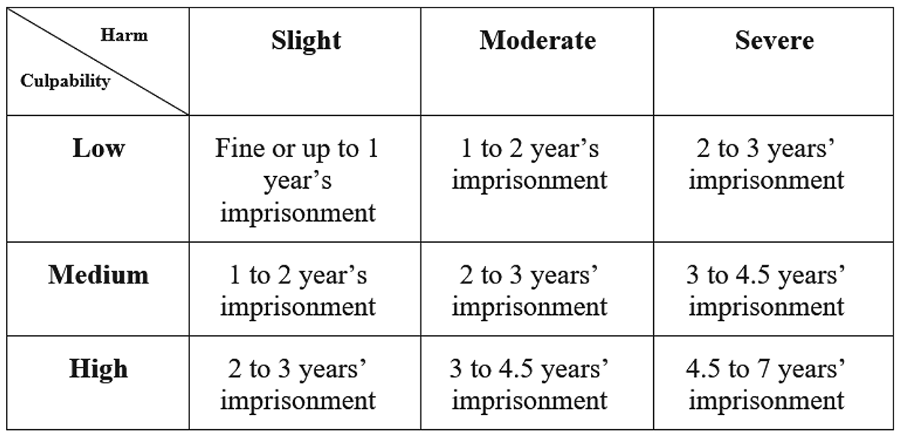

Second, based on the forecited factors, the Court will determine the indicative starting sentencing range:

Lastly, the Court will make further adjustments to the indicative starting sentencing range by considering the relevant aggravating and mitigating factors (the following is a non-exhaustive list):

| Offender-Specific Factors |

| Aggravating Factors | Mitigating Factors |

| – Offences taken into consideration for sentencing purposes – Relevant antecedents – Evident lack of remorse | – A guilty plea – Co-operation with authorities – Actions taken to minimise harm to victims |